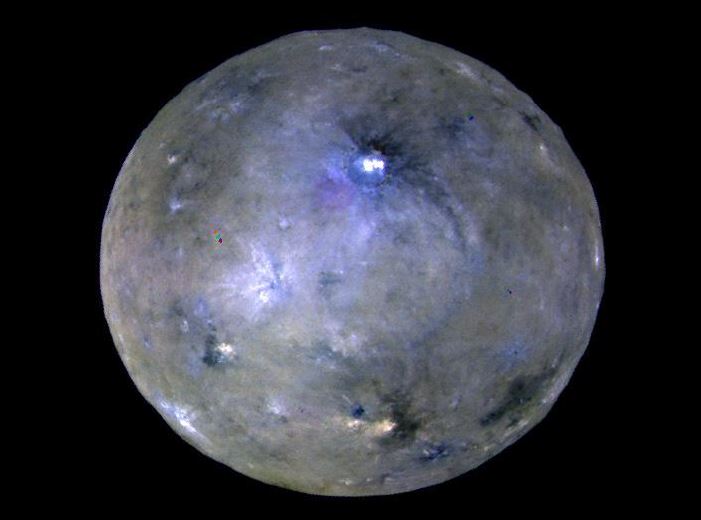

Caption: This image captured by the Dawn spacecraft is an enhanced color view of

Caption: This image captured by the Dawn spacecraft is an enhanced color view of

Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt. Credit: NASA/JPLCaltech/

UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA

There are millions of pieces of rocky material left over from the formation of our solar

system. These rocky chunks are called asteroids, and they can be found orbiting our Sun.

Most asteroids are found between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. They orbit the Sun in a

doughnut-shaped region of space called the asteroid belt.

Asteroids come in many different sizes—from tiny rocks to giant boulders. Some can

even be hundreds of miles across! Asteroids are mostly rocky, but some also have metals

inside, such as iron and nickel. Almost all asteroids have irregular shapes. However, very

large asteroids can have a rounder shape.

The asteroid belt is about as wide as the distance between Earth and the Sun. It’s a big

space, so the objects in the asteroid belt aren’t very close together. That means there is

plenty of room for spacecraft to safely pass through the belt. In fact, NASA has already

sent several spacecraft through the asteroid belt!

The total mass of objects in the asteroid belt is only about 4 percent the mass of our

Moon. Half of this mass is from the four largest objects in the belt. These objects are

named Ceres, Vesta, Pallas and Hygiea.

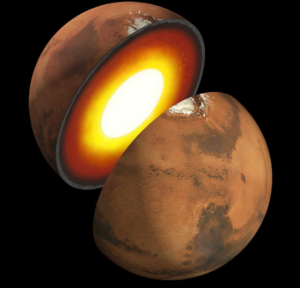

The dwarf planet Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt. However, Ceres is still

pretty small. It is only about 587 miles across—only a quarter the diameter of Earth’s

moon. In 2015, NASA’s Dawn mission mapped the surface of Ceres. From Dawn, we

learned that the outermost layer of Ceres—called the crust—is made up of a mixture of

rock and ice.

The Dawn spacecraft also visited the asteroid Vesta. Vesta is the second largest object in

the asteroid belt. It is 329 miles across, and it is the brightest asteroid in the sky. Vesta is

covered with light and dark patches, and lava once flowed on its surface.

The asteroid belt is filled with objects from the dawn of our solar system. Asteroids

represent the building blocks of planets and moons, and studying them helps us learn

about the early solar system.

For more information about asteroids, visit: https://spaceplace.nasa.gov/asteroid