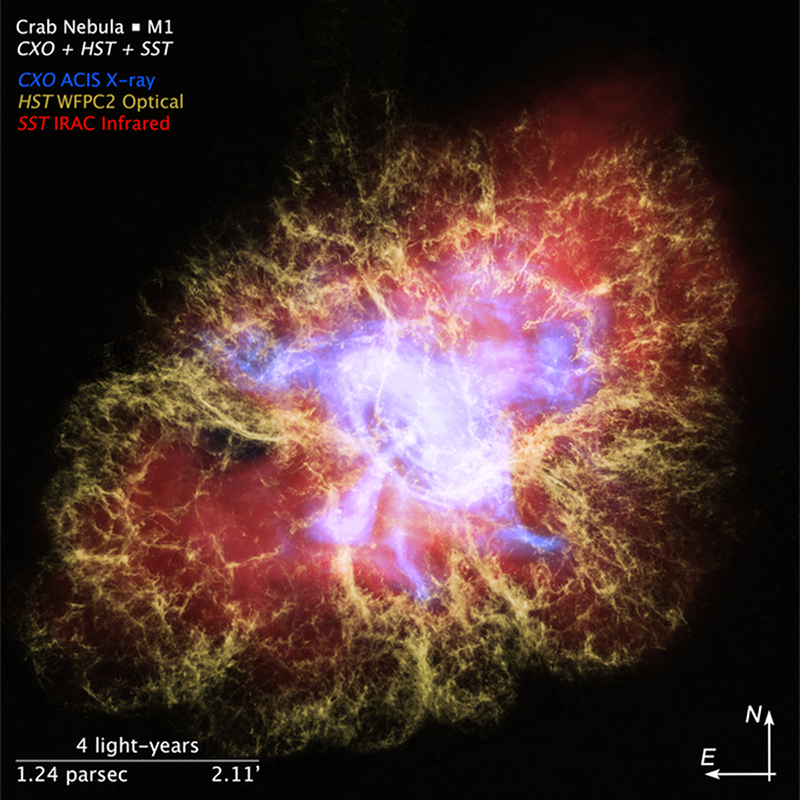

This image of the Crab Nebula combines X-ray observations from Chandra, optical observations from Hubble, and infrared observations from Spitzer to reveal intricate detail. Notice how the violent energy radiates out from the rapidly spinning neutron star in the center of the nebula (also known as a pulsar) and heats up the surrounding gas. More about this incredible “pulsar wind nebula” can be found at bit.ly/Crab3D Credit: NASA, ESA, F. Summers, J. Olmsted, L. Hustak, J. DePasquale and G. Bacon (STScI), N. Wolk (CfA), and R. Hurt (Caltech/IPAC)

By: David Prosper

What happens when a star dies? Stargazers are paying close attention to the red giant star Betelgeuse since it recently dimmed in brightness, causing speculation that it may soon end in a brilliant supernova. While it likely won’t explode quite yet, we can preview its fate by observing the nearby Crab Nebula.

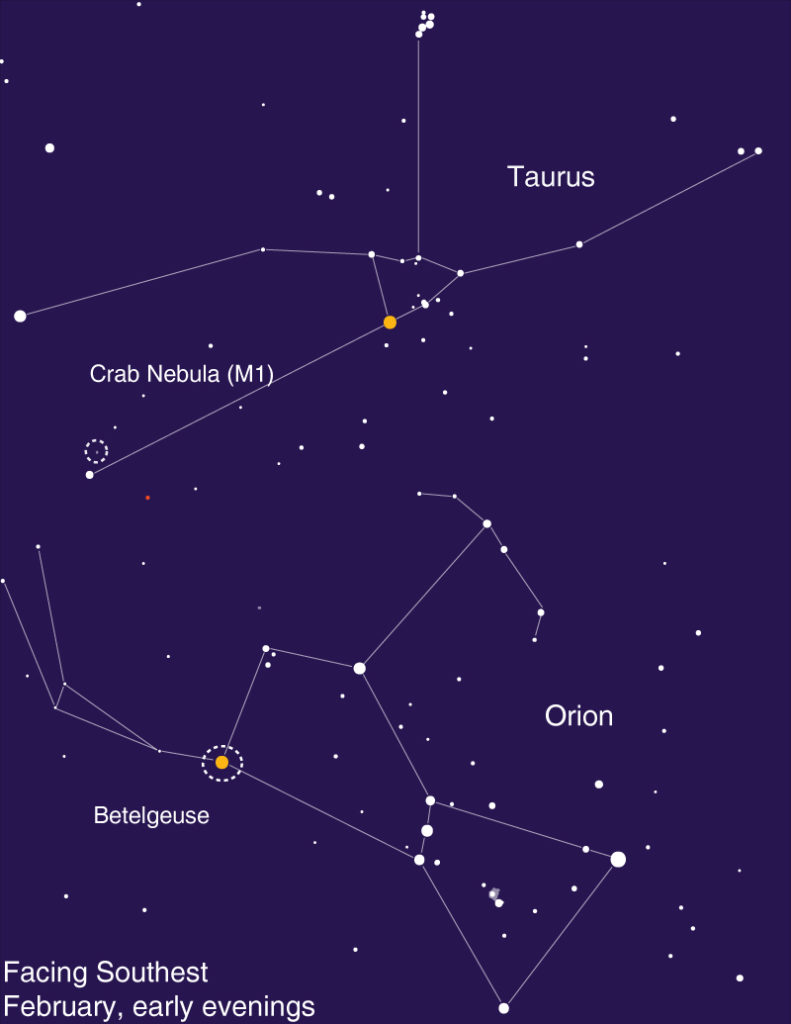

Betelgeuse, despite its recent dimming, is still easy to find as the red-hued shoulder star of Orion. A known variable star, Betelgeuse usually competes for the position of the brightest star in Orion with brilliant blue-white Rigel, but recently its brightness has faded to below that of nearby Aldebaran, in Taurus. Betelgeuse is a young star, estimated to be a few million years old, but due to its giant size it leads a fast and furious life. This massive star, known as a supergiant, exhausted the hydrogen fuel in its core and began to fuse helium instead, which caused the outer layers of the star to cool and swell dramatically in size. Betelgeuse is one of the only stars for which we have any kind of detailed surface observations due to its huge size – somewhere between the diameter of the orbits of Mars and Jupiter – and relatively close distance of about 642 light-years. Betelgeuse is also a “runaway star,” with its remarkable speed possibly triggered by merging with a smaller companion star. If that is the case, Betelgeuse may actually have millions of years left! So, Betelgeuse may not explode soon after all; or it might explode tomorrow! We have much more to learn about this intriguing star.

The Crab Nebula (M1) is relatively close to Betelgeuse in the sky, in the nearby constellation of Taurus. Its ghostly, spidery gas clouds result from a massive explosion; a supernova observed by astronomers in 1054! A backyard telescope allows you to see some details, but only advanced telescopes reveal the rapidly spinning neutron star found in its center: the last stellar remnant from that cataclysmic event. These gas clouds were created during the giant star’s violent demise and expand ever outward to enrich the universe with heavy elements like silicon, iron, and nickel. These element-rich clouds are like a cosmic fertilizer, making rocky planets like our own Earth possible. Supernova also send out powerful shock waves that help trigger star formation. In fact, if it wasn’t for a long-ago supernova, our solar system – along with all of us – wouldn’t exist! You can learn much more about the Crab Nebula and its neutron star in a new video from NASA’s Universe of Learning, created from observations by the Great Observatories of Hubble, Chandra, and Spitzer: bit.ly/CrabNebulaVisual

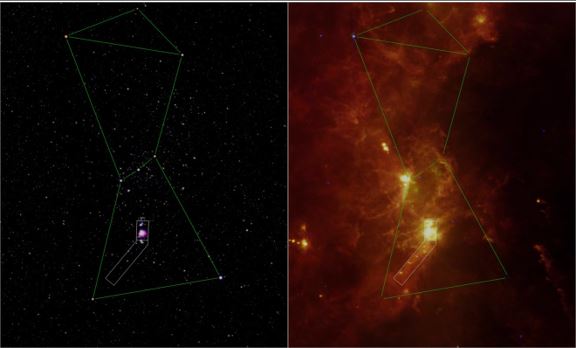

Our last three articles covered the life cycle of stars from observing two neighboring constellations: Orion and Taurus! Our stargazing took us to the ”baby stars” found in the stellar nursery of the Orion Nebula, onwards to the teenage stars of the Pleiades and young adult stars of the Hyades, and ended with dying Betelgeuse and the stellar corpse of the Crab Nebula. Want to know more about the life cycle of stars? Explore stellar evolution with “The Lives of Stars” activity and handout: bit.ly/starlifeanddeath .

Check out NASA’s most up to date observations of supernova and their remains at nasa.gov

Spot Betelgeuse and the Crab Nebula after sunset! A telescope is needed to spot the ghostly Crab.