By Jane Houston Jones and Jessica Stoller-Conrad

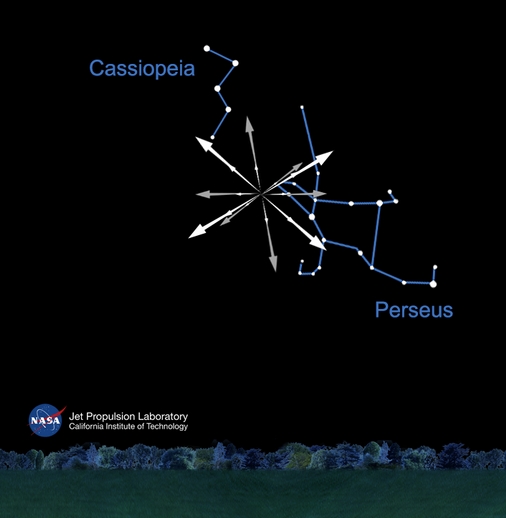

Caption: This illustration shows how the summer constellations trace a path across the Milky Way. To get the best views, head out to the darkest sky you can find. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Feeling like you missed out on planning a last vacation of summer? Don’t worry—you can still take a late summertime road trip along the Milky Way!

The waning days of summer are upon us, and that means the Sun is setting earlier now. These earlier sunsets reveal a starry sky bisected by the Milky Way. Want to see this view of our home galaxy? Head out to your favorite dark sky getaway or to the darkest city park or urban open space you can find.

While you’re out there waiting for a peek at the Milky Way, you’ll also have a great view of the planets in our solar system. Keep an eye out right after sunset and you can catch a look at Venus. If you have binoculars or a telescope, you’ll see Venus’s phase change dramatically during September—from nearly half phase to a larger, thinner crescent.

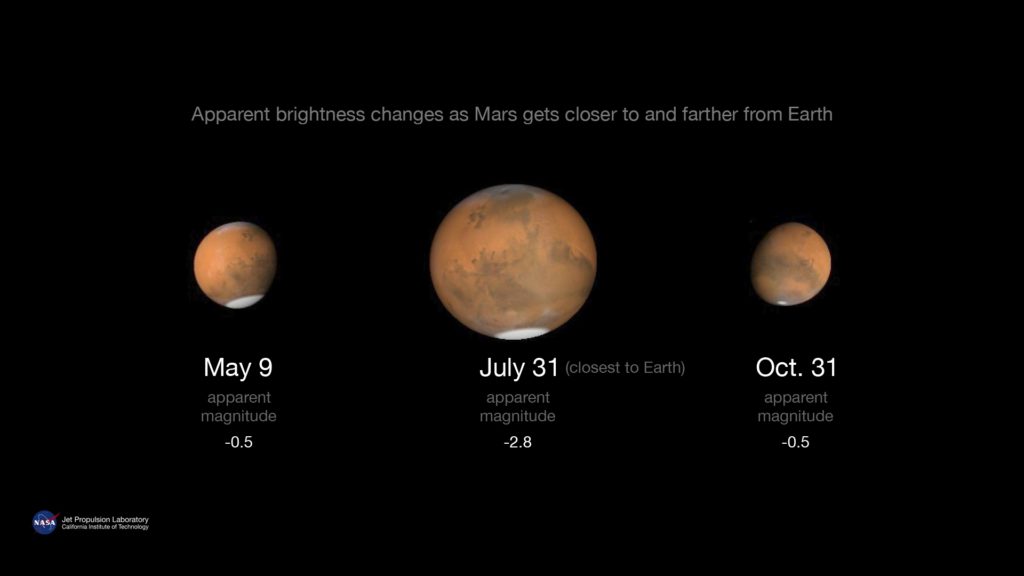

Jupiter, Saturn and reddish Mars are next in the sky, as they continue their brilliant appearances this month. To see them, look southwest after sunset. If you’re in a dark sky and you look above and below Saturn, you can’t miss the summer Milky Way spanning the sky from southwest to northeast.

You can also use the summer constellations to help you trace a path across the Milky Way. For example, there’s Sagittarius, where stars and some brighter clumps appear as steam from a teapot. Then there is Aquila, where the Eagle’s bright Star Altair combined with Cygnus’s Deneb and Lyra’s Vega mark what’s called the “summer triangle.” The familiar W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia completes the constellation trail through the summer Milky Way. Binoculars will reveal double stars, clusters and nebulae all along the Milky Way.

Between Sept. 12 and 20, watch the Moon pass from near Venus, above Jupiter, to the left of Saturn and finally above Mars!

This month, both Neptune and brighter Uranus can also be spotted with some help from a telescope. To see them, look in the southeastern sky at 1 a.m. or later. If you stay awake, you can also find Mercury just above Earth’s eastern horizon shortly before sunrise. Use the Moon as a guide on Sept. 7 and 8.

Although there are no major meteor showers in August, cometary dust appears in another late summer sight, the morning zodiacal light. Zodiacal light looks like a cone of soft light in the night sky. It is produced when sunlight is scattered by dust in our solar system. Try looking for it in the east right before sunrise on the moonless mornings of Sept. 8 through Sept 23.

You can catch up on all of NASA’s current—and future—missions at www.nasa.gov