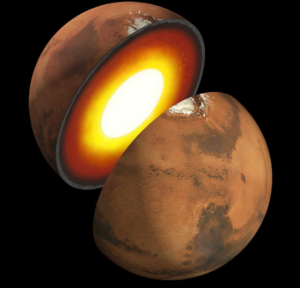

Caption: An artist’s illustration showing a possible inner structure of Mars. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Mars is Earth’s neighbor in the solar system. NASA’s robotic explorers have visited our neighbor quite a few times. By orbiting, landing and roving on the Red Planet, we’ve learned so much about Martian canyons, volcanoes, rocks and soil. However, we still don’t know exactly what Mars is like on the inside. This information could give scientists some really important clues about how Mars and the rest of our solar system formed.

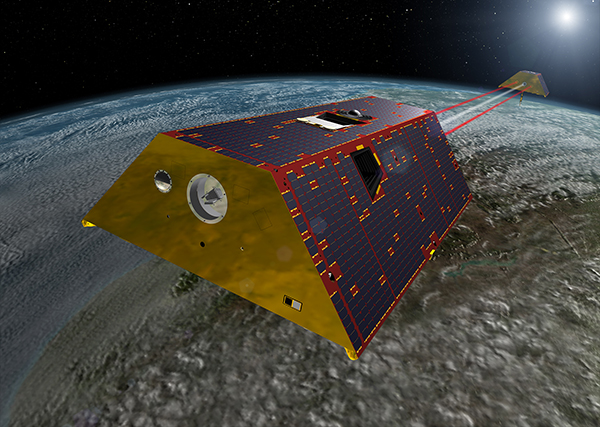

This spring, NASA is launching a new mission to study the inside of Mars. It’s called Mars InSight. InSight—short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport—is a lander. When InSight lands on Mars later this year, it won’t drive around on the surface of Mars like a rover does. Instead, InSight will land, place instruments on the ground nearby and begin collecting information.

Just like a doctor uses instruments to understand what’s going on inside your body, InSight will use three science instruments to figure out what’s going on inside Mars.

One of these instruments is called a seismometer. On Earth, scientists use seismometers to study the vibrations that happen during earthquakes. InSight’s seismometer will measure the vibrations of earthquakes on Mars—known as marsquakes. We know that on Earth, different materials vibrate in different ways. By studying the vibrations from marsquakes, scientists hope to figure out what materials are found inside Mars.

InSight will also carry a heat probe that will take the temperature on Mars. The heat probe will dig almost 16 feet below Mars’ surface. After it burrows into the ground, the heat probe will measure the heat coming from the interior of Mars. These measurements can also help us understand where Mars’ heat comes from in the first place. This information will help scientists figure out how Mars formed and if it’s made from the same stuff as Earth and the Moon.

Scientists know that the very center of Mars, called the core, is made of iron. But what else is in there? InSight has an instrument called the Rotation and Interior Structure Experiment, or RISE, that will hopefully help us to find out.

Although the InSight lander stays in one spot on Mars, Mars wobbles around as it orbits the Sun. RISE will keep track of InSight’s location so that scientists will have a way to measure these wobbles. This information will help determine what materials are in Mars’core and whether the core is liquid or solid.

InSight will collect tons of information about what Mars is like under the surface. One day, these new details from InSight will help us understand more about how planets like Mars—and our home, Earth—came to be.

For more information about earthquakes and marsquakes, visit:

https://spaceplace.nasa.gov/earthquakes