Astronaut Tim Peake on board the International Space Station captured this image of a CubeSat deployment on May 16, 2016. The bottom-most CubeSat is the NASA-funded MinXSS CubeSat, which observes soft X-rays from the sun—such X-rays can disturb the ionosphere and thereby hamper radio and GPS signals. (The second CubeSat is CADRE — short for CubeSat investigating Atmospheric Density Response to Extreme driving – built by the University of Michigan and funded by the National Science Foundation.) Credit: ESA/NASA

Big Science in Small Packages

By Marcus Woo

About 250 miles overhead, a satellite the size of a loaf of bread flies in orbit. It’s one of hundreds of so-called CubeSats—spacecraft that come in relatively inexpensive and compact packages—that have launched over the years. So far, most CubeSats have been commercial satellites, student projects, or technology demonstrations. But this one, dubbed MinXSS (“minks”) is NASA’s first CubeSat with a bona fide science mission.

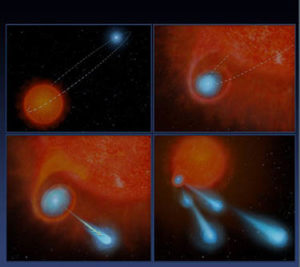

Launched in December 2015, MinXSS has been observing the sun in X-rays with unprecedented detail. Its goal is to better understand the physics behind phenomena like solar flares – eruptions on the sun that produce dramatic bursts of energy and radiation.

Much of the newly-released radiation from solar flares is concentrated in X-rays, and, in particular, the lower energy range called soft X-rays. But other spacecraft don’t have the capability to measure this part of the sun’s spectrum at high resolution—which is where MinXSS, short for Miniature Solar X-ray Spectrometer, comes in.

Using MinXSS to monitor how the soft X-ray spectrum changes over time, scientists can track changes in the composition in the sun’s corona, the hot outermost layer of the sun. While the sun’s visible surface, the photosphere, is about 6000 Kelvin (10,000 degrees Fahrenheit), areas of the corona reach tens of millions of degrees during a solar flare. But even without a flare, the corona smolders at a million degrees—and no one knows why.

One possibility is that many small nanoflares constantly heat the corona. Or, the heat may come from certain kinds of waves that propagate through the solar plasma. By looking at how the corona’s composition changes, researchers can determine which mechanism is more important, says Tom Woods, a solar scientist at the University of Colorado at Boulder and principal investigator of MinXSS: “It’s helping address this very long-term problem that’s been around for 50 years: how is the corona heated to be so hot.”

The $1 million original mission has been gathering observations since June.

The satellite will likely burn up in Earth’s atmosphere in March. But the researchers have built a second one slated for launch in 2017. MinXSS-2 will watch long-term solar activity—related to the sun’s 11-year sunspot cycle—and how variability in the soft X-ray spectrum affects space weather, which can be a hazard for satellites. So the little-mission-that-could will continue—this time, flying at a higher, polar orbit for about five years.