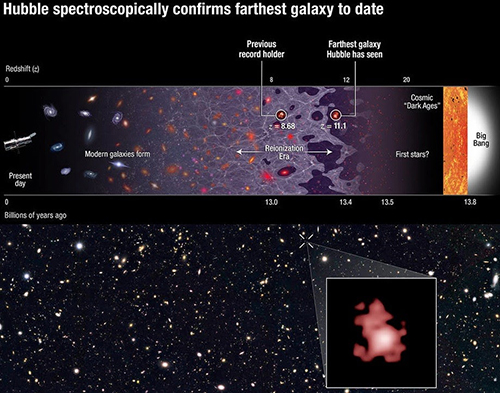

Images credit: (top); NASA, ESA, P. Oesch (Yale University), G. Brammer (STScI), P. van Dokkum (Yale University), and G. Illingworth (University of California, Santa Cruz) (bottom), of the galaxy GN-z11, the most distant and highest-redshifted galaxy ever discovered and spectroscopically confirmed thus far.

The farther away you look in the distant universe, the harder it is to see what’s out there. This isn’t simply because more distant objects appear fainter, although that’s true. It isn’t because the universe is expanding, and so the light has farther to go before it reaches you, although that’s true, too. The reality is that if you built the largest optical telescope you could imagine — even one that was the size of an entire planet — you still wouldn’t see the new cosmic record-holder that Hubble just discovered: galaxy GN-z11, whose light traveled for 13.4 billion years, or 97% the age of the universe, before finally reaching our eyes.

There were two special coincidences that had to line up for Hubble to find this: one was a remarkable technical achievement, while the other was pure luck. By extending Hubble’s vision away from the ultraviolet and optical and into the infrared, past 800 nanometers all the way out to 1.6 microns, Hubble became sensitive to light that was severely stretched and redshifted by the expansion of the universe. The most energetic light that hot, young, newly forming stars produce is the Lyman-α line, which is produced at an ultraviolet wavelength of just 121.567 nanometers. But at high redshifts, that line passed not just into the visible but all the way through to the infrared, and for the newly discovered galaxy, GN-z11, its whopping redshift of 11.1 pushed that line all the way out to 1471 nanometers, more than double the limit of visible light!

Hubble itself did the follow-up spectroscopic observations to confirm the existence of this galaxy, but it also got lucky: the only reason this light was visible is because the region of space between this galaxy and our eyes is mostly ionized, which isn’t true of most locations in the universe at this early time! A redshift of 11.1 corresponds to just 400 million years after the Big Bang, and the hot radiation from young stars doesn’t ionize the majority of the universe until 550 million years have passed. In most directions, this galaxy would be invisible, as the neutral gas would block this light, the same way the light from the center of our galaxy is blocked by the dust lanes in the galactic plane. To see farther back, to the universe’s first true galaxies, it will take the James Webb Space Telescope. Webb’s infrared eyes are much less sensitive to the light-extinction caused by neutral gas than instruments like Hubble. Webb may reach back to a redshift of 15 or even 20 or more, and discover the true answer to one of the universe’s greatest mysteries: when the first galaxies came into existence!